When the Local Becomes Global

In my second year at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I discovered that I could accurately pinpoint the confluence of my seemingly disjointed interests in fashion. It was an equally unnerving and moving revelation, which over the past year or so, I have followed relentlessly. I delved deeply into the intricacies and vices that have inherently become a part of the industry, and I was granted the opportunity to travel to New Delhi and Jaipur, India, to study the intersection of sustainability and fashion.

As production augments to meet the demands of a larger consumer base, waste management, greenhouse gas emissions, and water contamination are among some of the incredibly pertinent environmental concerns that surge as a result of the fashion industry. In many ways, these crises have not yet been addressed but in countries like India, confronting them cannot wait.

It was only our second day in New Delhi when I was overcome by some of the most intense anxiety I have experienced in recent memory. As we, four American students, stumbled out of our Uber onto the side of an incredibly busy road, I immediately understood why our driver had asked if this was the correct drop off destination. As I looked down the alleyway in front of me, I was confronted by the Ghazipur Landfill.

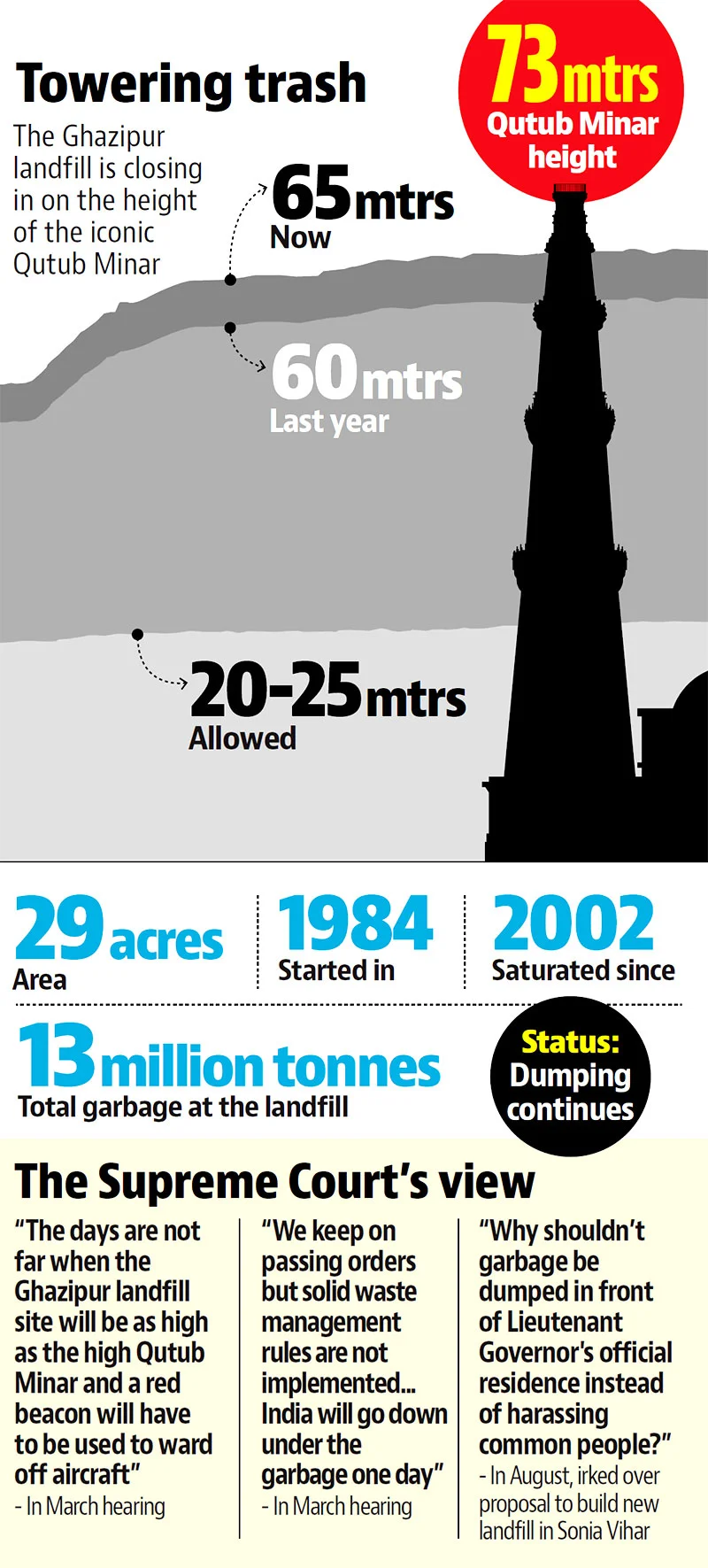

Towering over 65 meters, the Ghazipur Landfill is notoriously known as the “Mountain of Garbage.” Massive vultures swooped down too close for comfort multiple times and as my legs began to quiver, I became increasingly overwhelmed by its prominence. I was soon unable to speak or move.

Until then, I had only contextualized fashion from the academic and creative perspectives I interacted with daily. Suddenly though, it became clear to me that the industry I had come to revere, could not be separated from these most tangible implications of rampant production and mass consumerism. While my anxiety subsided as quickly as I hopped into another car, I knew that this very escape was an act of immense privilege that many individuals living in nearby communities could not access with ease.

Clothes, as designer Orsola de Castro states, are “our chosen skin.” Though there are various relevant cultural factors at play, the fashion industry has largely fallen into a vicious cycle of production, distribution, consumption, and disposal – paving the way for the institution of fast fashion. Fast fashion is a term used to describe clothing that is being produced cheaply to maximize on trends. While this is a relatively new phenomenon, it has rapidly taken hold of the industry.

Historically, the fashion industry has had two seasons – fall/winter and spring/summer. Today, rather than taking months to produce designs, brands like H&M, Urban Outfitters, and Zara are launching new product lines weekly.

Individuals around the globe are collectively consuming around 80 billion new articles of clothing each year. Garments are being worn less and less and being disposed of at higher rates than ever before. Even the fibers favored by fast fashion brands, particularly polyester and nylon, could take up to a thousand years to biodegrade. Through documentaries like The True Cost, these environmental impacts surrounding fast fashion have not only been disseminated widely, but they have become accessible to most consumers – inspiring urgency from even the most unlikely of characters.

While many of these problems could be remedied if major brands altered their habits and made substantial reparations for the destruction they have caused, the path forward is not quite as simple.

Many innovators in the fashion world believe that efforts to re-localize economies could present a feasible opportunity for achieving sustainability in the coming years. Through localized economies, the industry could inspire a reversion from the mechanistic modes of production and consumption, that are integral to fast fashion’s prominence, towards ones based on community.

Thousands of miles away from where this story started, I was back in Chapel Hill, a relatively small town that I have had the opportunity to call home for the past three years. Once again, I found myself ingrained in a culture that has already been working towards the arduous process of reframing the industry and its practices. Students studying at the university have assumed integral roles in this movement as activists, entrepreneurs, and disruptors. These individuals are addressing the implications of the fashion industry by investing in the local community and emboldening their peers to take action.

In the fall of 2017, Chandler Simpson and Emma Scalise had just started their academic careers at the University of North Carolina. Through accounts of their upbringings, the two quickly uncovered their shared love of fashion and a desire to enact change through it. Just as they began to explore ways to pursue their mutual interests, they noticed an evident gap in the UNC sustainability community – a fashion organization. For the rest of that semester, the two began to develop what would become the Sustainable Fashion Initiative.

By springtime, SFI was an established student organization at the university. Though it was difficult to define exactly how they would manifest their vision at first, Simpson and Scalise’s intentions were sincere – educate UNC students about the social and environmental impacts of the fashion industry and empower them to be activists in their own way.

Existing predominantly in the advocacy space, their team began to conceive of ways to not only address the issues they felt strongly about but to make a concerted effort to welcome those who traditionally felt excluded from these conversations.

“I think people kind of overestimate how much others know and understand. It’s not that they’re apathetic, I truly believe that many just don’t know. I was the person who could have easily said ‘oh, I just didn’t care in high school,’ because I was not surrounded by this at the time. We know who we’re trying to engage. Our goal is to make things as accessible as possible for everyone,” said Simpson.

Through speaker panels, to upcycling and repurposing workshops, and onto collaborations with other fashion-related groups, SFI has acted as a connector between these organizations.

On March 31, 2019, they furthered this synergy by hosting a clothing swap in collaboration with Rumors Boutique, a local thrift shop. Individuals arrived at the porch outside of the store and donated, purchased, and swapped articles of clothing. Intending to improve upon the relatively unsustainable donation market, the event expanded the lifespan of many products and established a creative space for individuals to reflect on their personal styles.

“In a big way, we have built a community of people who are really passionate about this issue. One thing that we have tried to do is make our mission, and the information we share at meetings, tangible through these different events that we host. They allow us to expand our sense of community beyond just UNC,” said Scalise.

Groups like the Sustainable Fashion Initiative are galvanizing students at the university to take action. Today, this increased awareness has inspired other student-led initiatives at the university to thoughtfully reuse products for social good.

Phoenyx is a sustainable fashion company, run by students, that designs durable bags and accessories from rescued vinyl billboards, and other recycled materials, while empowering the Chapel Hill community.

Alessandro Uribe-Rheinbolt is a UNC student from Bogotá, Colombia, who has been using his love of sewing to bring this venture to life. Uribe-Rheinbolt primarily works as a designer and manages the entire creative process – from conception, to production, to end-of-life.

“I’ve been sewing a lot these past couple weeks just prototyping all the bags that we hope to mass-produce one day. So, we’re working on a duffel bag, on a few backpack designs, and others still in the development phase. But the ones that are pretty much set are the pencil cases; they’ve been tested, and we’ve made several copies,” said Uribe-Rheinbolt.

Phoenyx’s ultimate mission is two-fold: reducing environmental waste while creating fair and accessible employment opportunities for the most disenfranchised.

According to Uribe-Rheinbolt, billboard vinyl cannot be recycled because of the greenhouse gases it emits when broken down or burned. Though thousands of pounds of waste are produced from billboard vinyl each year, it is largely left sitting in landfills for decades. Phoenyx’s founders realized the potential for economic and environmental gain and have been harnessing the positive qualities of these discarded billboards since.

“There are other companies making bags, but we have not seen anything like this in the South. We basically have access to every billboard that’s put up in North Carolina. We are just trying to make use of the excess in the industry to fight against what would otherwise end up in a landfill,” he said.

As manufacturing costs are relatively low, Phoenyx plans to invest the most in their labor by providing a living wage for workers. In May, they will hire their first community member in partnership with the Community Empowerment Fund, a student-run non-profit organization that enables and sustains transitions out of homelessness and poverty.

“In Chapel Hill, rent prices are really high and it’s affecting many of the community members who, if they are being paid a minimum wage, have to work around 80 hours a week to pay for a two-bedroom apartment. We wanted to emphasize that and keep it local,” said Uribe-Rheinbolt.

While very different in their approaches, SFI and Phoenyx have dedicated themselves to reducing the ecological footprint of the Chapel Hill community, mitigating social stigmas, and fostering community – something the fashion industry desperately needs more of.

Lizzie Russler, an incoming senior at the University of North Carolina, has devoted much of her young adult life to sustainability initiatives both in Chapel Hill and beyond. Through her experiences with Sephora and Reconsidered, she has had the opportunity to view consumer goods from a wide array of lenses. In her self-designed, semester-long independent study about the fashion industry and sustainability, she analyzed McKinsey and Company’s The State of Fashion 2019. In this report, created a partnership with the Business of Fashion, 2019 was declared as a year of awakening for the industry.

“The ‘awakening’ of the industry refers to, in my opinion, this shifting in the paradigm of fashion. To be successful and relevant, brands cannot be complacent. I think this will require actors to face a constantly changing world by committing to radical transparency that encourages conscious consumerism,” said Russler.

As communities begin to implement practices that reimagine metrics of success and profit, the new paradigm of the fashion industry will demonstrate how powerful collective action can be in shifting economies and norms. Together, this fervor could inspire drastic change across the board by reducing waste, sourcing sustainable fabrics, exploring distribution alternatives, innovating end-of-life systems, and promoting a circular economy.

While serving as the Creative Director of a student-run apparel brand called Vintage Blue, I have been emboldened by the students and community members that are embarking on this journey towards a new paradigm in the fashion industry. As students attend alternative dyeing workshops, promote buying secondhand, and apply in mass numbers to join teams on these organizations, the excitement on campus is palpable. Though the movement is not as widespread as many would like it to be, the attention and action I have been surrounded by have provided me with some solace that our local actions could ultimately yield the upheaval of a global institution.

“Sustainable fashion looks a little different for everyone. Simply though, sustainability is the new paradigm of fashion. The industry as a whole is changing, consumers are changing. Although just the start, we, the fashion industry and its consumers, are making the transition,” said Russler. “But now, the question is: is it happening fast enough?”